The Art and Engineering of Screw-Making, Repair, and Finishing in Gunsmithing

In gunsmithing, screws are more than simple fasteners—they are integral components that influence the performance, aesthetics, and safety of a firearm. From custom screw creation to repair and finishing, each detail requires exacting standards, especially for high-stress parts like action screws, scope mounts, and other attachments. This in-depth guide explores everything from screw-making and thread pitch to advanced repair techniques and achieving perfectly aligned screws.

For gunsmiths handling worn screws during restorations or custom builds, the sections on repair and aesthetic restoration will provide advanced techniques to help you bring screws back to their factory-new condition.

Essential Tools for Precision Screw-Making and Repair

To achieve professional results in screw-making and repair, the following tools are essential:

Lathe: For precision thread and diameter cutting, ensuring accurate fit.

Micrometer: Allows ultra-precise measurements down to 0.0001 inches, critical for pitch diameter verification.

Caliper: Provides quick measurements of the outer diameter (OD) and hole diameters in firearms.

Thread Pitch Gauge: Essential for identifying and verifying imperial and metric threads.

Screw Slot File: Designed for creating precise, uniform slots; critical for aesthetics and functionality.

Brownells Screw Checker: A tool for quickly checking common screw sizes and pitches in firearms.

Machinery’s Handbook: The go-to reference for unified screw threads, tolerances, and fit classes.

Understanding Thread Pitch and Tolerance

Imperial vs. Metric Threads

In American-made firearms, thread pitch is often measured in threads per inch (TPI). For instance, a 1/4"-28 screw has a 0.25-inch diameter and 28 threads per inch. Metric threads are measured by the distance between threads in millimeters, like an M6 x 1.0 screw, which has a 6mm diameter with 1mm spacing between threads.

Pitch Diameter and Fit Class

Loose Fit (Class 1): Rarely used in gunsmithing, as it allows for too much play and can loosen under vibration.

Standard Fit (Class 2): Ideal for general-purpose threading; sufficient for non-critical components.

Precision Fit (Class 3): Preferred for firearms, as it offers a tight, vibration-resistant engagement critical for scope mounts, action screws, or other high-stress components.

Measuring and Cutting Threads with Precision

We are not going in depth on how to cut a thread on a lathe with this post, but we will show some fixtures and blanks screw kits we use.

Screw holders

Threading fixture shop made

Screw Timing for Aesthetic Alignment

Aligning screw slots adds to the firearm’s professionalism and aesthetic. Here’s how to achieve it:

Mark the Pre-Fit Position: Insert the screw, marking the slot position before fully tightening.

Adjust Screw Length: File the underside of the screw head incrementally until the slot aligns perfectly.

Use Shims if Necessary: Shims under the screw head can prevent over-rotation not ideal.

Secure Final Fit with Loctite: Apply a small amount of blue Loctite to ensure stability without permanent bonding for most applications in firearms.

Advanced Techniques for Screw Repair

Gunsmiths often face two primary forms of screw damage: deformed slots and stripped threads. Here’s how to restore them.

Repairing Damaged Screw Slots

One of the most common forms of damage to firearm screws is a “mushroomed” or deformed slot, usually caused by using the wrong screwdriver or excessive torque. Here’s how to repair a damaged screw slot:

Repositioning Displaced Metal:

When a slot is damaged, material is often displaced rather than removed. Using a small gunsmith’s hammer with a polished face and tap the deformed metal back into place. This technique pushes the displaced metal back into the slot area, allowing you to reform the slot rather than remove material.

Position the screw securely in a screw-holding fixture to prevent it from slipping. A vise with soft metal jaws or screw-holding jig is ideal for this, as it keeps the screw stable during repair. We have a vise that we replaced the steel hardened jaw face with copper.

Filing the Slot:

Once the displaced metal has been realigned, use a screw slot file (chosen to match the slot width and depth) to carefully re-cut the slot. Start with light, controlled strokes, keeping the file perfectly aligned with the slot orientation to avoid further deformation. Hack saw blade may fit as well.

Pay close attention to depth and width to maintain uniformity across all screws in the firearm. Check your progress frequently, and avoid over-filing, as you want to keep the slot deep enough for a proper screwdriver grip without compromising the screw’s integrity.

Polishing the Screw Head:

After restoring the slot, the head of the screw may need polishing. Place the screw in a drill chuck, securing it so that the head faces outward. Set the drill to a low speed and use progressively finer grits of sandpaper (start around 200 grit and move to 400 grit) to polish the head.

Rotate the screw at a steady speed and apply the sandpaper evenly, keeping pressure light to avoid changing the head’s shape. This method removes any small scratches or tool marks left from the repair process, giving the screw head a smooth, uniform finish.

Restoring Stripped Threads

Minor Thread Repair with a Die: Clean up stripped threads with a threading die that matches the TPI and diameter. Use cutting oil and gentle alignment to restore the thread shape.

Using Thread Inserts: For some stripped holes, especially in soft metals, a thread repair insert like a Heli-Coil can restore original dimensions.

Preventive Measures for Screw Longevity

Select the Correct Screwdriver: Gunsmithing screwdrivers are precisely sized to prevent slippage. The top one is a standard flat screwdriver the bottom is a gunsmithing screwdriver that have parallel surfaces.

Tap the Screwdriver Handle: Tap when removing stubborn screws to reduce slot damage.

Use Penetrating's oils: Kroil is a good oil we use. We will let the oil soak for 10 -15 mins and sometimes over night. We have also uses some heat to thin it out to get it to weep into the threads.

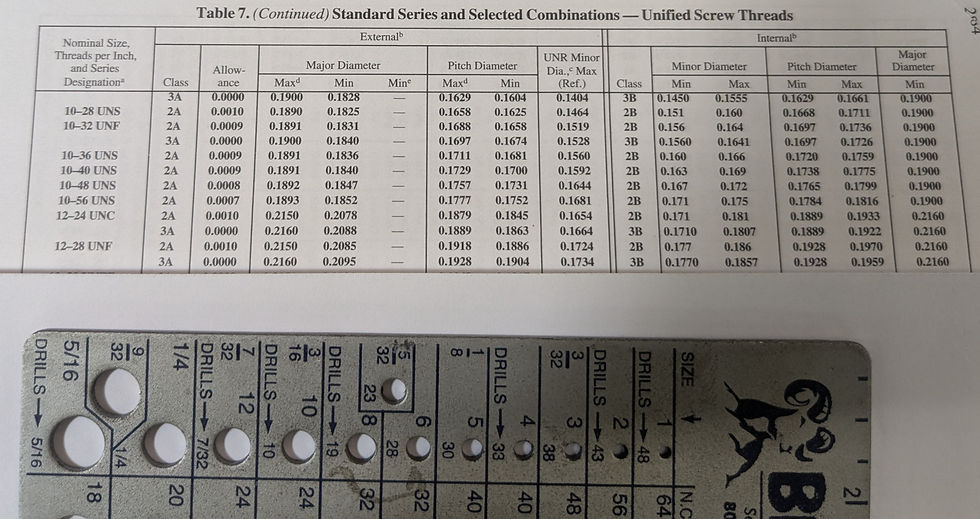

Using Reference Tools: Brownells Screw Checker and Machinery’s Handbook

The Brownells Screw Checker helps identify screws quickly. By threading a screw into the checker’s various holes, you can match its size and pitch without guesswork, a great asset for working with unknown screws.

The Machinery’s Handbook offers tables with exact specifications, tolerances, and fit classes. For instance, a 12-28 thread specification will list the major, minor, and pitch diameters for each fit class. Gunsmiths can reference these tables to ensure screws meet industry standards, achieving consistent results across projects.

Key Concepts and Techniques for Timing Screws

These techniques are also used to time barrels to receivers and muzzle breaks to barrels.

Understanding Screw Advancement per Turn

Advance per Turn: For a screw with 28 TPI (threads per inch), each complete turn advances the screw by approximately 0.0357 inches.

MATH: 1 / 28 = .0357

Advance per Degree: Since there are 360 degrees in a full turn, each degree advances the screw linearly by:

Advance per degree = 0.0357 / 360 ≈ 0.0000992

These calculations allow you to estimate how far the screw needs to rotate in degrees to align the slot precisely.

Adjusting Screw Length to Control Alignment

If the slot is slightly off alignment, carefully filing the underside of the screw head can help advance the slot to the desired position.

Calculate the Required Adjustment: Lets say the 28 TPI screw needs to turn a 1/4 turn to be aligned.

MATH: 1/4 turn = 90 degrees

Advance for 90 degrees = 90 / 360 X .0357 = .0089 inches.

Carefully remove small amounts of material from the underside of the head, checking the alignment after each adjustment. This gradual approach allows for precise timing adjustments without compromising the screw’s structural integrity.

Using Shims for Consistency

If filing down the screw head isn’t practical, shims provide a controlled way to adjust alignment. Thin shims (available in various increments) placed under the screw head can prevent it from turning too far, enabling precise slot alignment without modifying the screw itself.

Calculate Shim Thickness: For example, a 28 TPI screw and a 45-degree adjustment is needed to line up screw slot, and a full turn (360 degrees) advances the screw by 0.0357 inches:

MATH: 1 / 28 = .0357

Advance for 45 degrees: 45 / 360 = 1 / 8 = .125

Shim thickness = .125 X .0357 = .0045

Using the calculated shim thickness allows you to control the final alignment accurately.

Testing and Final Torque Application

Install the screw to its intended position and verify that the slot aligns perfectly with other screws. Apply the final torque with a screwdriver or torque wrench.

Finishing Techniques: Cold Bluing and Nitriding

After repair, restore the screw’s appearance to match the firearm.

Cold Bluing: After polishing, apply cold bluing for a quick, corrosion-resistant finish. Rinse and oil for protection.

Nitriding: For a semi durable, high-end finish, consider salt bath nitriding for excellent corrosion resistance and uniform color.

Hot Salts Bluing: A more durable finishing process that produces a deep, polished blue-black color. It requires specialized equipment, but the results are resilient and visually striking, ideal for high-end firearms or restorations.

Parkerizing: A phosphate coating process that creates a matte, textured finish, ideal for firearms that require a rugged, non-reflective surface. This finish is especially popular for military or tactical-style firearms and screws, as it provides outstanding corrosion resistance.

Elevate Your Craft with Redleg Gunsmithing Services

At Redleg Guns, we believe in the art of precision. Whether creating custom screws or restoring damaged ones, our gunsmiths use advanced techniques to bring firearms to peak performance and aesthetics. If you’re ready to elevate your craft, contact us today for custom screw-making, repair, or restoration support.

Comments